weeknotes: sweepline post-mortem, hosting, reading

Bird.rs updates

The main update was implementing interpolation for the flight feathers of a bird wing. I previously had the primaries, secondaries, and tertials as independent definitions, but I realized that most of the images of bird wings feathers have a smooth interpolation between their shapes. Luckily, I have code that interpolates already, so I blended between the shapes of the groups of flight feathers.

One issue I have is that I evaluate points along every feather every frame using custom functions, and that determines the shape of the curve. But the underlying code (LazyNodeF32) is slow, so I tried a few things there: if I sample fewer total points, it’s faster, but I can’t get the round ends of feathers I need. If I shift those samples points towards the end of the feathers, it can look better with fewer points. Maybe the most blanket solution is that I now cache the feather designs, so when I’m not modifying the designs, it only needs to translate/rotate the feathers. That gets me above 30fps.

But I accideintally lost some of the control I had over the feather designs somewhere along the way. So I’m probably going to tuck the feathers into the wing for a bit longer until I can work that out.

In any case, I’m very close to having a female house sparrow! There are a bunch of real sparrows outside our lab’s window, and I think the female house sparrow has a cute, subtle eyeline. They also have interesting scapular patterns I need to implement!

Anisotropic

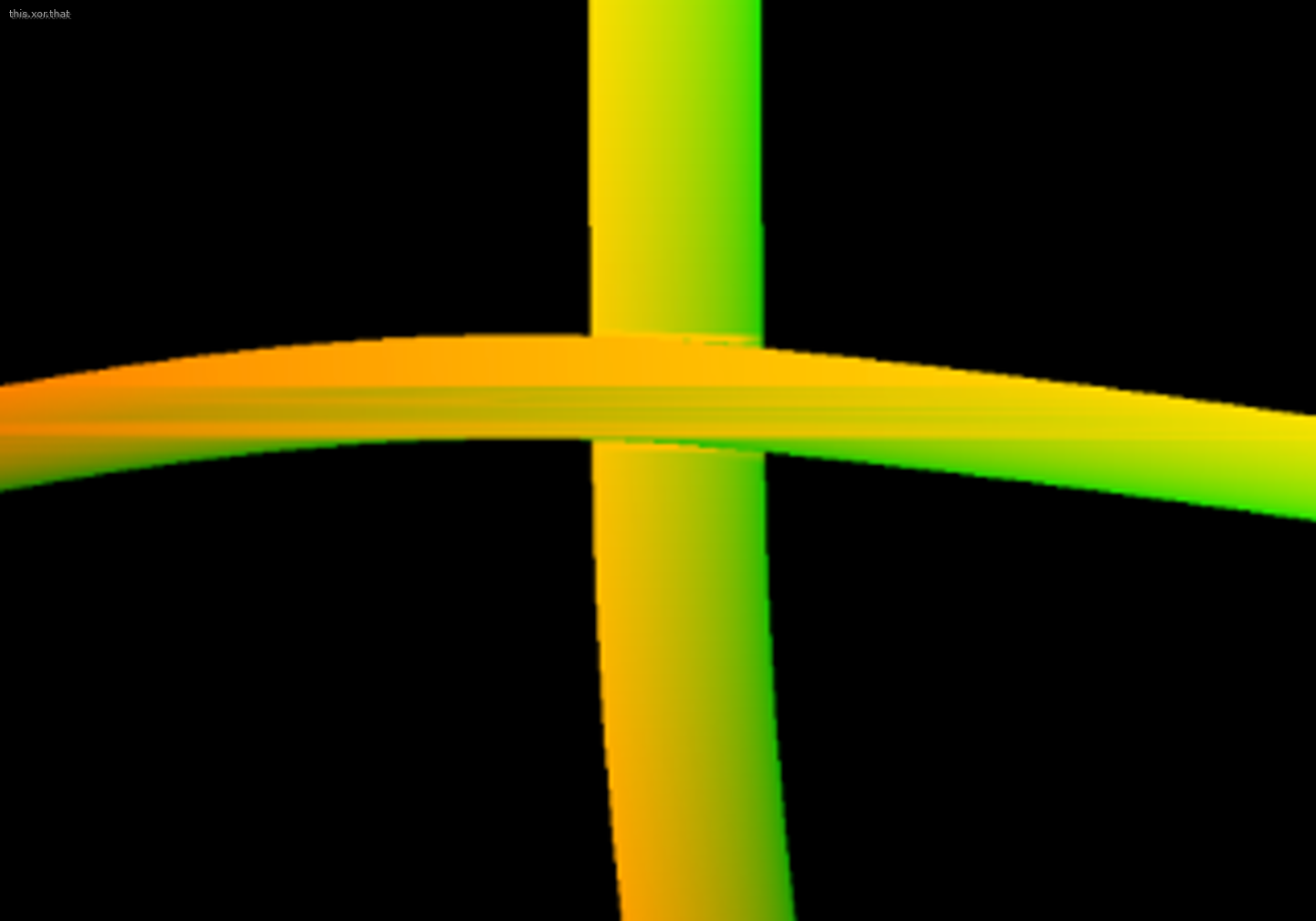

I’m still trying to texture map onto the ribbons.

I’m learning a lot of things (in other words, I do not know much about computer graphics), but here’s roughly what I’m finding. The thing Nannou and I use for 2d shape triangulation is lyon, which seems to work perfectly fine if you have a solid fill or a gradient that’s based on the xy location. I’m finding that once I do something a little different, like mapping the vertices based on the “distance in a curved thread” or the “distance from the center”, the triangles become obvious: you’ll get a long thin triangle that interpolates down the center of the string, next to other triangles that more nicely chop it up, and the border is obvious. I tried to insert degenerate triangles down the midpoint of the ribbon, but still had long triangles. I think it’s because lyon is using a type of decomposition that is very fast but also creates very long, ugly triangles

So I switched to a simple manual triangulation by following the ribbon strip. This is easy because the ribbon is already defined as a lot of quadrilaterals.

Then I got to the small irregular areas near where one ribbon is overlapped by another part of a ribbon. I considered fudging it by adding a big shadow from the upper thread, but ultimately decided I should try to texture it. I switched from lyon to delaunator, and the area is finally filled!

So! I have the simple case triangulated! I still need to work out a few last vertex values, and I think there are some bugs for more complicated shapes I’ll need to work out.

Hopefully, I’m nearing the end of my required triangulation work, and it won’t become like sweepline…

Post-mortem for Sweepline

Well, I got to replace a headache sweepline implementation with bounded volume hierarchy this week.

For the last few years, I shuddered when intersection detection came up. Oh sure, line segments intersecting is easy. Curves aren’t so bad either, because you can turn them into a sequence of line segments. But I had it in my head that the only way to iterate over those lists to find intersections was to use sweepline, e.g. Bentley–Ottmann algorithm. And because I often work with thousands of intersections all needing to be detected perfectly, or it looks wrong, I’ve been fighting with bugs and edge cases ever since. (Oh, you ordered things by slope, but now some things are vertical, so better handle that case.. Oh, now we have a line that passes exactly through where two line segments meet, better make sure that’s handled.)

This week, Zach suggested bounded volume hierarchy instead of sweepline, and within an hour, my code was working better, and even if some bugs remain, the code is much simpler.

I’ve been debugging sweepline periodically for at least a year, so I spent some brain cycles this week wondering what I got out of that. I find that part of my art practice involves implementing a lot of things from scratch. (But don’t get me wrong, I use plenty of libraries when I can!) Usually, it starts because I can’t find a Rust package, or I haven’t learned what to call the thing I’m doing. But I also like working out the mechanics of an algorithm in code, because that’s how I get a feel for the rhythm and shape of the code, and try to make that beautiful code feeling in my visuals. But besides just experiencing coding, I think it can be useful for the work: it puts my style in the visual output via quirks (and sometimes bugs).

On the other side, I want to use those algorithms for something, and if I spend all my time debugging the algorithm, I won’t make anything with it. I think the reason I’m so grumpy about sweepline is that I really needed a working intersection detection, and so I spent too much debugging it instead of taking a step back to think about other approaches, and usually, I think I’m pretty content with the balance I strike.

At least I got some cool plotter art out of it.

Here’s one of the art shows where I showed these buggy intersection detection implementations.

Here’s one of the art shows where I showed these buggy intersection detection implementations.

Hosting

With Glitch going away, a few school projects piling up that depend on a server, and finding out my “free hosting for life” doesn’t support Docker or Postgres, I started looking for hosting for the first time since I was a teenager. I ended up using my student discount for Digital Ocean to get something running. Things have come a long way, and it was almost fun to be setting up servers again.

What I’m reading

I finally read Karl Sim’s paper Evolving Virtual Creatures, and it was fun to see the list of equations they used to program the neurons of the creature.

I also read By Hand And Eye this week, which I had found a while back when I was trying to learn how to use a compass and straightedge and could only really find Sacred Geometry Youtube videos until I found these talking about how cabinetmakers would make a right angle before the industrial age. The book is a practical book about how furniture was designed, and a common thing that comes up is using proportions and subdividing a space. I learned a few tricks!

I have a feeling that many design resources stop at “4:3” or “golden ratio” or imply that we’re past that all that now that we have precise rulers and computers and an absurd number of digits of pi.

But a part of code art is about finding numbers that look nice, and there are a lot of public domain books from previous centuries about how (certain) people used to think about good shapes and compositions. It’s a nice place to start and look around from, and even if you’re skeptical like me that the proportions reflect some higher level natural beauty, it’s at least reflecting the ancient Greek/Roman influence on the shapes around us.